Australia-based The Conversation has featured an article by Marlene L. Daut, Professor of French and African American Studies at Yale University, in which she explores the historical and ongoing injustice of the “debt for independence” imposed by France on Haiti. Caliber.Az presents an analysis of the article.

In her article Daut, a scholar specializing in 19th-century Haitian history, highlights the systemic nature of this economic and moral extortion, showing how it severely impacted Haiti's development for generations. The article, an insightful commentary on the long-standing consequences of this imposed financial burden, argues that France owes Haiti reparations, not only as a moral responsibility but also as a material one.

The article begins by referencing a call made by Haiti’s former president Jean-Bertrand Aristide in 2002, demanding that France pay Haiti $21 billion for the indemnity imposed upon the country in 1825 in exchange for France’s recognition of Haiti’s independence. This figure, rooted in historical calculations, underscores the heavy financial toll that Haiti endured for simply asserting its sovereignty. Daut's article also connects this historical claim to more recent calls for reparations, including a request made by Leslie Voltaire, Haiti’s Transitional Presidential Council president in early 2025, and a tweet from tennis star Naomi Osaka, a person of Haitian descent.

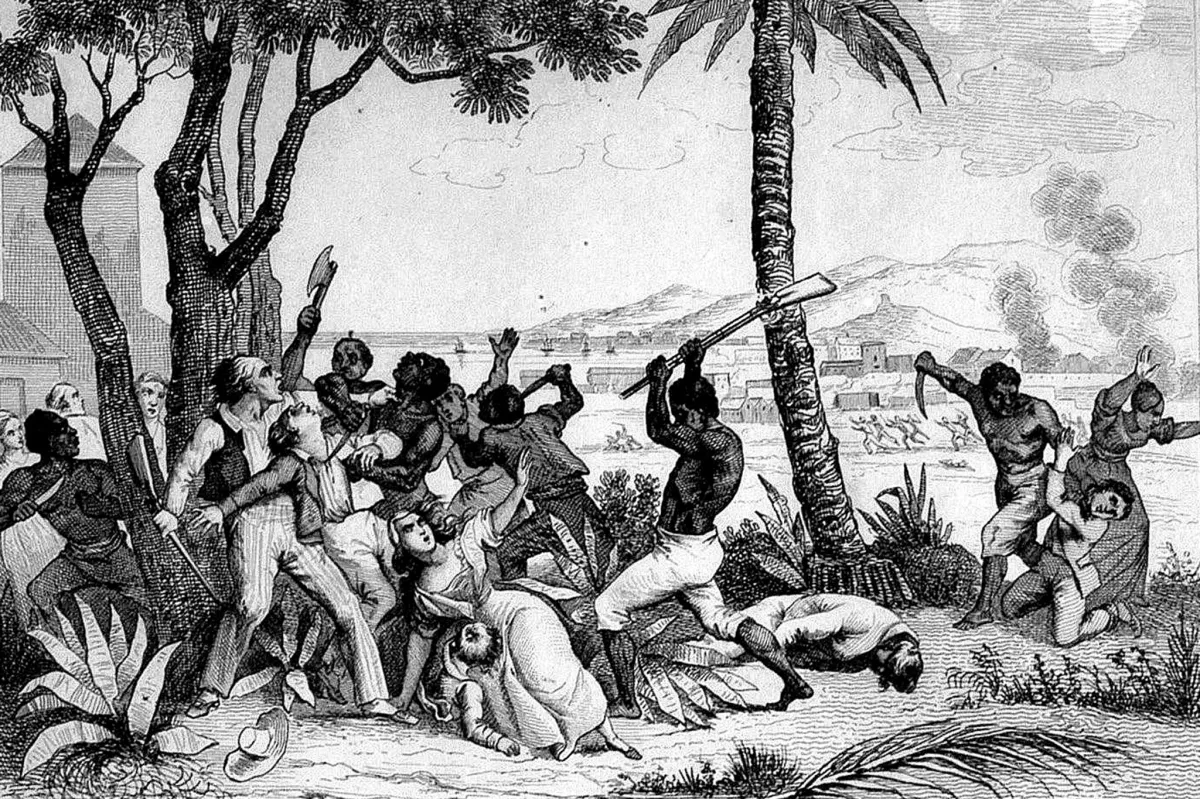

The narrative traces the historical background of the indemnity agreement. Haiti declared independence from France on January 1, 1804, after a successful revolution led by enslaved people in the French colony of Saint-Domingue (now Haiti). Daut contrasts Haiti’s brutal struggle for freedom with the French insistence on imposing a financial penalty on the newly-formed nation for the loss of its colony. This demand for reparations, which began as a claim by former French slaveowners, was ultimately enforced through coercion and the threat of military action.

Daut highlights the pivotal moment in 1825, when Charles X of France imposed a crippling indemnity of 150 million francs on Haiti for recognizing its independence. The sum was extraordinarily high—almost six times Haiti’s annual revenue—and was deliberately designed to cripple Haiti’s economy. As Daut explains, France’s recognition of Haitian independence came at an extortionate price, one that was financially unfeasible for the country. Haiti was forced to borrow from French banks to meet the first payments, further entrenching the country in debt. A subsequent reduction of the debt in 1838 only provided temporary relief, as the loan system continued to harm Haiti’s economic capacity.

The article also delves into the socio-economic consequences for Haiti. Daut points out that the funds extracted from Haiti had a devastating effect on its development, with the country failing to invest in infrastructure, education, and healthcare. The legacy of the debt and the resulting economic instability meant that Haiti could never fully recover or achieve the prosperity necessary for its citizens to live healthy, fulfilling lives. The toll of the debt was both immediate and long-term, manifesting in the systemic poverty that continues to affect the nation today.

A key moment in the article is Daut’s reference to the financial compensation France paid to former slaveowners after slavery was abolished in its colonies. By juxtaposing the payment of compensation to former French colonists and the extortion imposed on Haiti, Daut highlights the racial wealth gap that resulted from these actions. While France acknowledged the economic value of enslaved labor by compensating former slaveholders, Haiti was forced to pay for its freedom at an exorbitant price.

Daut’s inclusion of contemporary statistics—such as the staggering differences in poverty rates between Haiti, French overseas territories like Martinique and Guadeloupe, and mainland France—shows the long-term, concrete impacts of this historical injustice. She argues that these disparities are the direct result of the stolen labor of African ancestors and the economic suppression caused by the indemnity.

One of the most powerful parts of Daut’s analysis is her discussion of recent attempts by France to address its colonial past. While French presidents have occasionally acknowledged the need for reconciliation, they have generally downplayed or ignored the concrete economic restitution Haiti demands.

Daut points out that the French government, under President Emmanuel Macron, has made symbolic gestures but has largely avoided addressing the material costs of France’s actions. The upcoming “landmark statement” about France’s colonial legacy that Macron plans to release on the bicentennial of the indemnity agreement is viewed skeptically by Daut, as she believes that only tangible economic reparations will truly address the harm done.

In conclusion, Daut argues that France’s historical injustice against Haiti cannot be overlooked or downplayed. She insists that reparations should not be limited to symbolic acts or “memory initiatives” but must include real economic recompense. Daut’s analysis reinforces the idea that to deny the material consequences of slavery and colonialism is to deny the reality of France’s exploitative practices.

The article calls for France to not only acknowledge the wrongs committed but to also make amends through financial restitution for the suffering and economic deprivation Haiti has endured as a result of the “debt for independence.” The continued call for reparations, as articulated by Haitian leaders, activists, and scholars like Daut, serves as an important reminder of the need for historical justice.

In summary, Daut’s piece offers a compelling argument for why Haiti deserves reparations from France—both as a moral imperative and as a matter of economic justice. The historical context she provides demonstrates the lasting effects of the "debt for independence," while her critique of France’s response to Haiti’s calls for reparations highlights the deep inequalities that persist today.

Source: caliber.az